Gerry’s relationship with gravity was about to experience a change. His father, now a builder of bungalows in the ever expanding suburban development of rural Lindonshire, would be furious should he learn of Gerry’s latest pastime. Housing developments create building sites and these were then Gerry’s favourite ‘hang-outs’. He and his ‘mates’, a loose collection of similarly-minded neo-troglodytes would gather at the site of the newly delivered brick stack and epic works would then be conceived and constructed from a human-chain of industry and ingenuity. Should the brick stack arrive on the Friday before a Bank Holiday weekend then the resulting weekend’s work might rival the Taj Mahal for grandeur. At least in the eyes of the small army of mud warriors who would painstakingly see their grand vision take shape before the real builders were astonished by its immensity - shortly before the dawning realisation that they would have to deconstruct the miniature Hampton Court brick maze before their own labours could begin. It was not a popular discovery by builders and, safety implications aside, led to much damage and no few number of injuries.

It was astonishing, given the complexity of and tons of materials thus consumed, that no-one was actually killed by these finely-balanced but potentially lethal tombs. One simple misjudgement during their design or construction would result in the potential for burying a dozen children in a miniature Aberfan of bricks, blocks and planks. Multi-storey and subterranean constructions were attempted and tumbled on the failure of an angle or absence of a supporting beam. It was dirty, dangerous and exhilarating work, as the sandcastle imaginations of the boys stood back to survey the genius of their innocence as magnificent palaces of their dreaming asserted themselves across the vast acreage of their childhood.

The climbing of scaffolding was another popular diversion for the intrepid constructors and it was whilst jumping from the first storey of a half-built shell that Gerry had his first misadventure with the forces of gravity. Confident that the arc of his flight would ensure a soft landing in the awaiting pit of yellow, soft sand. He couldn’t quite account for his painful landing in the pile of bricks, adjacent to the grime-encrusted cement-mixer onto which he bounced. Gerry’s injuries might have been much worse than the broken wrist which, other than a few small bruises and scratches, was his painful and somewhat inconvenient souvenir of the mistimed leap into the unknown. A tree was blamed and conflict with his father thereby averted, but if Gerry was chastened, it was not to lead to a sudden and more profound understanding of Newton’s Law. That would require a tree.

The resident monkeys of Gerry’s expanding tribe were the Sadler boys. Stephen and his older brother Martin could climb anything. Trees, posts, walls and rocks were all powerless to resist the progress of these simian-like creatures who liked nothing better than to swing from the treetop of one-hundred feet high Poplar trees, changing from one swaying tree to another with the agility of an Orang-utan. Fear had obtained no purchase in their wild and free souls and they challenged every physical boundary without its restricting influence. It seemed quite natural for Gerry to be ascending the massive trunk of the old and extremely gnarled willow tree which stood at the centre of the park where the boys had gone in pursuit of excitement. The Sadler boys were never inclined to smoking or other nefarious activities, but Gerry shared their joie de vivre and their shared interest in music greased the wheels of friendship sufficiently for them to tolerate one another’s idiosyncrasies. Oddly enough, the boys’ father was a travelling salesman for a large tobacco company, but no-one in the family ever expressed any interest whatsoever in the products from which the family made its apparently comfortable living. Not as much as an ashtray betrayed their resistance to the superiority, or otherwise, of the products peddled by the amiable head of the family, Paul. Paul Sadler was fan of the great outdoors and his children would benefit from sharing this passion as the assembled canoes, wet-suits, hiking boots and self-constructed garden tree-house made evident.

Following Martin closely along the fork of the trees lowest truncation, Gerry had perhaps hoped to learn more of the gecko-like techniques possessed by his friend. In the event his attention was suddenly completely focussed on the ground some eighteen feet directly below him. Climbing up a tree was easier than climbing along a thick bough and he began to perspire in a way he hadn’t previously experienced. The cold sweat dripped into his eyes and made his hands slippery as he tried to remove it with the backs of his fingers. He sat now astride the thick bough, swaying slightly in the movement of the light summer breeze. His friend, crouched easily just beyond his reach. “You alright Gez?” enquired the relaxed but concerned Martin.

“No, not really Mart. I feel a bit dizzy to be honest” and as Gerry moved to wipe the latest drips of anxious sweat from his brow his weight shifted imperceptibly and he slid sideways off the trunk, like a wounded Beau Geste having finished his last mounted report from a besieged desert fort. The fall was a blur of whirling and rotating madness before Gerry’s twisting body hit the mercifully soft earth but with such force all the air spilled urgently from his lungs. His body, breathless and apparently lifeless was soon the scene of great concern as his friends and passing adults gathered around the prone body of the fallen boy. When he came to, Gerry remembers the heavy feeling of his body, almost as if he had fallen deeper into the earth, beyond his own physical frame, from whence he could never entirely return to the same specific gravity he had previously felt. He felt heavier, and very, very earthy.

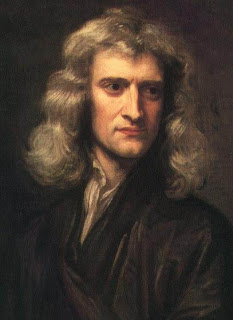

His practical demonstration of the inescapability of Sir Isaac Newton’s theory, made real, Gerry never again felt comfortable around exposed heights. Mr Rudkin, the Physics teacher however did not want a discourse on gravity when apprehending Gerry coming into school on his friend Martin’s unicycle, demanding only to know “What are you doing boy?”.

“I am cycling into school and learning Newton’s Law sir!” Gerry replied as he cycled expertly up the single narrow ramp and parked the offending article.

“Well, you can’t come to school on one of those, can you?” Mr Rudkin enquired uncertainly.

“Apparently so sir. I just did!” replied the delighted Gerry.

The discussion ended, uncharacteristically for Gerry without further rebuke, but he could not help but notice how any individualism he ever displayed was automatically met with an institutionally ordered wall of approbation. It was almost as if everyone in the school was engaged in a conspiracy to reveal the flaws of each child and then, having labelled and assessed their unsuitability, write their destiny in spitefully measured disregard. He’d never had a disagreement with Mr. Rudkin, though many would follow, but he felt judged as a troublemaker when his actions might just as well have excited pleasure, even joy, at the unpredictable event. Yes, he’d got away with it, but he was no stranger to implied criticism - his own father’s specialisation - which he now found himself resenting.

Of course he’d had other ‘run-ins’, as his father habitually characterised them, with several teachers. Doctor Michaels, a mountainous Welshman with a chinstrap black beard and comb-over, initially made some attempt to accommodate the talkative but likeable first-year, but his paper-thin patience soon exhausted itself on the paper-sharp wit of his new intake of chatty pupils. A bout of chalk-throwing by the irascible Welshman didn’t seem to solve the problem and the inevitable collateral damage inflicted on the girls unfortunate enough to be behind Gerry might have led to complaints from the innocent girls’ parents. Finally, during one hectic Monday morning, the good Doctor took leave of his senses and threw a long and potentially lethal haymaker at the astonished Gerry’s head. His reactions were luckily for his own health and the Doctor’s reputation, equal to the assault, and with a deft roll of his head, the huge fist and thick wrist, whistled past the boys head, connecting instead on the wide sweep of its arc, with the laboratory tap which promptly snapped in two gushing its contents forth in an aerial fountain of suddenly released pressure.

The good Doctor tried to discuss his growing frustration with Gerry at the boy’s apparent attention deficit and ever present need to be ‘the centre of attention’, but, as Gerry tried to reason with him whilst slightly distracted by his teacher’s bandaged hand, throwing chalk, blackboard-rubbers and haymakers in his direction were questionable tactics on this basis alone. Before the giant Welshman’s patience could again reach its margins, Gerry stopped making the eye-contact, so desired by those with an apparent curiosity to better know his mind and the conversation ended uneasily in a detention for Gerry which seemed odd to him when only his teacher had so dramatically misbehaved.

Gerry had ceased taking his grievances to the high court of his father’s judgement when he realised that his own father’s pre-occupations would rule against him with the tired eyes of a man who was himself more than slightly out of lock-step with the prevailing belief in all things institutional. His father railed against the Government and its new notion of ‘comprehensive’ education, a new paradigm that Gerry himself was an unwitting victim to.

His second year at school was shared with the arrival of a very distinct and new group, the comprehensive students themselves, and with them an entirely new educational structure and set of conflicting demands. The new children, no longer required to demonstrate their ‘suitability’ for Westeven Grammar, either educationally or socially, arrived in great numbers, swelling the schools population to the very extremities of its capacity. The existing staff, unprepared for this invasion were hard-pressed to contend with what many of them felt to be a dilution of their purpose, aims and abilities. The two independent syllabi were to be taught, and administered, in tandem, to a widely differentiated twin cohort of ability and as it proved difficulty. Many teachers, such as the much vaunted Mr. Cant, realised immediately the impossibility of the competing demands and swollen rolls of these competing agendas, and in time, simply gave up and moved on to new pastures. Others, less aware of their own limitations, imposed themselves upon the new directive with leech-like authority. They were there and they meant to stay there. This saw the rise to local power of the worst sort of teacher. Those with ambition but without conscience. The school bullies rose like slag to the top of the furnace from where they spilled their caustic embers upon all those who resisted the new education ministry’s imperative. All children were equal, but some teachers were somehow more equal than others.

Gerry enjoyed reading his first novel, George Orwell’s Animal Farm at school that year, at least in the months following the surprise and shocking departure of Miss Markham. Her very public breakdown, in room 6/7 had occurred one Thursday morning when the despised and spider-like spinster had literally unravelled in front of Gerry’s class. Teachers and students who witnessed the drama would often attribute the moment of crisis to the question that Gerry asked his teacher.

“Is that brandy I can smell Miss?” he had enquired, quite ingenuously, familiar as he was with the aroma of the spirit from his several close encounters with Dr. Humphrey Dickman, the family GP, who made no attempt to disguise his favourite tipple which reeked from his mouth when under the close proximity of one of his examinations.

He never did receive the courtesy of a reply as the poor old girl first slumped into her chair and then, in an ever increasing crescendo of sobbing, declared herself unfit to continue her career. Several distressing minutes passed before two of the more ‘sensible’ girls left the scene of the cacophonous keening, returning with the deputy headmistress, Violet Richardson, a dwarf-like lady who effected the twin-set and pearls era of education, along with an impressive growth of facial hair that might well have qualified her for a circus career had education not afforded her a suitable sinecure. Realising the very real distress to both Miss Markham and the children, Aunty Vi, as she was genuinely affectionately known, dismissed the children early for their lunch break and set about making Miss Markham’s last morning at school as easy as possible. The children last saw her as she was winched up on the tail-lift of the ambulance which had been summoned to take her away. She was strapped into the seated position of her wheelchair and displaying a cracked smile from within the cocoon of her hospital pink, crocheted blanketed comfort of her madness which was plain to see reflected in the staring and unashamedly curious faces of the hundred or so children who had gathered to witness this humiliating departure.

Mr. Winwood of course had to conduct a post mortem investigation of the circumstances relating to her embarrassing departure and unsurprisingly Gerry was summoned to an audience with him. Gerry, having given a very straight-forward account of his conversation with the departed madwoman was more than slightly bemused at the head’s attempt to connect him with the breakdown, regarding him as the straw which broke the camel’s back.

“Oh no sir, it wouldn’t have been anything I said. It’s the growing class-sizes and the conflicting demands of teaching both comprehensive and grammar school students at the same time” he confidently replied.

“I beg your pardon Hood?” queried the by now perplexed head teacher.

“Yes sir, I heard Miss Markham discussing it last week with her head of department and they both agreed that their workload has become ridiculous and that they never get any time to catch-up with the requirements of senior management. You can ask any of the teachers sir, they’re all talking about it.” he replied without any sense of awkwardness, knowing how closely that this fitted his own father’s analysis of the ‘cock-up that this Government calls education’ on which he regularly held forth across the pages of his newspaper or during the BBC’s six-o’-clock news.

“You don’t seem to appreciate the gravity of this situation.” Mr. Winwood told Gerry, across the steel framework of his semi-elliptical glasses.

“Oh yes sir, I do.” said Gerry and was about to embark on a discourse about the discovery by Sir Isaac Newton and the theory to which this led, all of which he had learned in Mr. Rudkin’s dissertation of the subject in fact, when Mr. Winwood produced a large stick from behind his desk.

“Bend over my desk boy” ordered the cold and unemotional voice that threaded itself like a worm into their conversation.

The sudden change in subject and atmosphere came as a surprise to Gerry, but deep within him a new survival instinct had begun its process and Gerry was surprised to then discover himself holding the large and weighty glass ashtray that sat on the front corner of the head’s desk.

“What are you doing with that boy?” demanded the tremulous tenor of the head’s voice.

“Well sir, if you try to hit me with that, I will hit you back with this!” declared the frightened but defiant voice that shook from a previously unheard depth within him

“I BEG YOUR PARDON?” screamed the enraged head teacher as the stick shook threateningly from his outstretched and pointed arm that held it aggressively out before him.

“Well you started it sir! If you are entitled to attack me with a stick, I am entitled to use a weapon to defend myself!” a voice from deep within Gerry declared.

“I am suspending you from this school forthwith!” commanded the head, by which time Gerry had reversed out of his office, leaving his weapon on the bookcase by the entrance as he walked quickly toward the cloakroom to collect his bag, happy to obey the head’s most recent edict.

His father, grieving the recent loss of his beloved mother, was unable to arouse the usual degree of ire that Gerry might have expected from the latest development in his educational interruption, and allowed the incident to pass with only the muttered rejoinder that he agreed with Mr. Winwood’s response and therefore sanction of two weeks suspension because as Mr. Winwood had correctly surmised Gerry simply didn’t ‘understand the gravity of the situation’. His latest experiential meanderings in the bewildering world of Newtonian physics had taught Gerry something much more important, he felt. That equal and opposite forces were as much at his disposal as bullies such as Mr. Winwood, and Miss Markham, and he now knew how to employ such forces in his defence.

No comments:

Post a Comment